Transcript - How The Administrative State Is Disputing Your Right To A Jury Trial

Today on Legalese, are talking about a case that may be the most important Supreme Court case this term. So lets discuss a case that is poised to strike at the most contemptable aspects of the administrative state. From their threat to our individual rights and civil liberties, including, but not limited to, the fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth and fourteenth amendment, and the dissolution of separation of powers among the branches of the federal government..

Greetings and welcome to Legalese. Today we are covering what I believe may wind up being the most interesting and consequential cases for this Supreme Court Term. Securities and Exchange Commission v Jarkesy. We briefly covered the QP in this case as part of my Supreme Court roundup video. Today we are taking a deep dive and we have a whole lot to dive into.

First we will be discussing the background of the case, including the fascinating holdings in this case when it came before the fifth circuit last year. Which the Supreme Court case is simply seeking to either affirm or vacate.

Then we will be discussing what can be gleaned from the oral arguments in this case that were heard on November 29th.

I will be addressing and debunking some of the more common scare mongering that has arisen with this case.

Finally, I will be giving you my own take on this case. So stay tuned, because we have a hell of a lot to cover.

Administrative State

Fundamentally speaking, The administrative state is a term used to describe the power that some government agencies have to write, judge, and enforce their own laws.

But first, I want to take just a moment to define exactly what I mean by Administrative Agency, Administrative law, and administrative state.

In the government of this commonwealth, the legislative department shall never exercise the executive and judicial powers, or either of them; the executive shall never exercise the legislative and judicial powers, or either of them; the judicial shall never exercise the legislative and executive powers, or either of them; to the end it may be a government of laws, and not of men.[1]

Constitution of Massachusetts, October 25, 1780

You may be wondering what an archaic article from the declaration of the rights of the Inhabitants of Massachusetts, from their 1780 Constitution has to do with this very new legal concept that Is the administrative state…

Fundamentally speaking, The administrative state is a term used to describe the power that some government agencies have to write, judge, and enforce their own laws.

We no longer have a government of laws. This dissolution of the separation of powers to such a degree is the very thing identified by classical Republicans from Machiavelli to Montesquieu to Madison identified as one of the worst of all tyrannies.

Although the Constitution vests all legislative powers in the legislative branch, Congress has delegated much of its lawmaking capacity to an alphabet soup of regulatory agencies. Ostensibly under presidential oversight. (Think EPA, SEC, FDA, etc.) Amazingly, there is no official count of how many executive branch agencies are making policy, though estimates reach as many as 430. Regardless of their exact number, hundreds of federal agencies [are] inserting themselves into every nook and cranny of daily life. Agencies regulate through a combination of the legislative, executive, and judicial functions by issuing rules with the force of law, policing those rules, and adjudicating their enforcement.

In 2021, for example, the Biden administration issued 3,257 regulations with the force and effect of law, whereas Congress passed 81 laws during that time. That works out to be over 40x more regulations being created than new laws being passed. While supporters of the administrative state will point to these same figures as a matter of pride-- As they talk about the efficiency of administrative agencies doing the work a so-called “do nothing” Congress refuses to.

But Congress’ inability to pass laws is a feature, not a flaw. The administrative state is an end run around what is supposed to be a difficult process. Our bicameral legislature is one of the most important and most effective checks on the power of the federal government.

The last available year for comprehensive data about administrative adjudications is 2013, when the five busiest agencies convened 1,351,342 executive branch tribunals; that same year, there were 57,777 total cases (civil and criminal) filed in the U.S. district and appellate courts. That’s more than 23x more agency adjudications than Article III federal court trials.

Of course, the administrative state’s concentration of legislative, executive, and judicial power operates in considerable tension with our constitutional structure, which was designed to diffuse government authority to better protect liberty. As James Madison warned in Federalist no. 47

“The accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands . . . may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny.”[2]

Administrative agencies have always been an important part of our government from day one, but what we call the administrative state is a conception that has grown in fits and bursts at various times over our nation’s history. Though this growth was most prominent during the progressive era from the late 19th to early 20th century, than again during the new Deal era.

But the most important and consequential moment came with the passage of the Administrative Procedures Act of 1946. This statute is often referred to the “constitution of the administrative state.”

When the APA was passed in 1946, agencies rarely issued legislative rules; instead, agencies created rules through case-by-case adjudication, akin to how the common law works. As a result, the APA gives scant attention to rulemakings, which is now the primary means by which agencies regulate. The absence of meaningful procedural safeguards has abetted what attorney and administrative law professor Gary Lawson has dubbed the rise (and rise) of the administrative state. It was this shift from case by case adjudication to broad legislative rulemaking as their primary focus over the next several decades that first gave birth to administrative law. It really wasn’t until the early 1970s that people began to recognize what we now call administrative law as its own unique and comprehensive body of laws.

Besides promulgating law like regulations, agencies also enforce these rules in prosecutions before tribunals located within the same agency that brought the enforcement action. This combination of prosecutorial and adjudicative authority coexists uneasily with our constitutional structure. As Madison observed in Federalist 47, and Montesquieu before him in Spirit Of The Law—

Again, there is no liberty, if the judiciary power be not separated from the legislative and executive... Were it joined to the executive power, the judge might behave with violence and oppression.

~Montesquieu, Spirit of the Laws, Book 11, Chapter 6

In practice, the agencies’ home-field advantage is sometimes conspicuous. For example, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) acts both as the prosecutor and the judge when the agency pursues financial penalties through enforcement of its regulations for publicly traded companies and investment activities. According to an analysis conducted by the Wall Street Journal, the SEC had a 90 percent win rate in contested cases it brought before its own internal administrative law judges (Often simply referred to as an ALJ) from 2010 through 2015, while it prevailed in only 69 percent of federal court trials over the same period. During this period, regulated parties filed an official complaint regarding an alleged lack of impartiality by one SEC in-house judge, whose record ruling in favor of the agency had been 51-0.

Case Background

Congress has given the Securities and Exchange Commission substantial power to enforce the nation’s securities laws, and its decisions have broad consequences for personal liberty and property rights. But the Constitution constrains the SEC’s powers by protecting individual rights and the prerogatives of the other branches of government. This case is about the nature and extent of those constraints in securities fraud cases in which the SEC seeks penalties.

The SEC brought an enforcement action within the agency against George Jarkesy for securities fraud. An SEC ALJ adjudged Jarkesy liable and ordered various remedies, and on appeal, the same ALJ reaffirmed his own ruling (imagine that!) following Jarkesy’s appeal over several constitutional arguments that he raised. The first thing that made this case stand out to me was how the fifth circuit handled the case. Usually, when a petitioner brings a case seeking review of a lower court decision the Judge hearing the case will try to resolve the case as narrowly as possible. That is not what happened here. The fifth circuit issued three separate decisions, all as alternative holdings, and each of which is a very big and important decision that will not just affect the SEC necessarily, but could affect the entire administrative state. So lets review the three alternative holdings made by the fifth circuit then briefly discuss them one by one.

We hold that—

(1) the SEC’s in-house adjudication of Petitioners’ case violated their Seventh Amendment right to a jury trial;

(2) Congress unconstitutionally delegated legislative power to the SEC by failing to provide an intelligible principle by which the SEC would exercise the delegated power, in violation of Article I’s vesting of “all” legislative power in Congress; and

(3) statutory removal restrictions on SEC ALJ violate Take Care Clause of Article II.[3]

This case started with the SEC bringing a fraud case against Jarkesy. And the question was about the authority of the SEC, the first holding concerned the right of a jury trial under the Seventh Amendment, because the SEC has accused him of fraud. The Fifth Circuit held that securities fraud was similar enough to common law fraud, that existed at the time of the founding, as such, the Seventh Amendment right to a jury trial was triggered in this case.

The second decision in this case concern non-delegation, which is a big deal because here they employed non delegation to actually block an action taken by administrative agencies, which is rather rare. Generally, non-delegation is used to construe statutes narrowly to limit the authority of the agency in certain contexts. But that's not what the Fifth Circuit did.

Here, Congress had given the SEC the authority to make a regulation with the same force as law as congressional legislation and they used that power to create a regulation that is functionally identical to the existing criminal offense of fraud at common law. The most important difference is this regulation gave them a choice that common law does not provide. They have the authority to decide whether to bring the case in an Article Three court with full authority of all the protections afforded to a defendant in that case. (For instance, in an Article III Court invoking your fifth amendment right to not answer questions cannot be held against you or be construed as evidence of guilt.)

The other option Congress gave was to try this case as an administrative proceeding, all handled internally by the very agency brining the charges. Administrative proceedings provide none of the constitutional or common law rights of a criminal defendant in an Article III Court (As such, Invoking your erstwhile right to silence in administrative proceedings can and will he held against you as positive evidence of guilt.)

In the Jarkesy case, what we have is an agency, the SEC, exercising legislative authority to write a regulation (with the force of law) that Jarkesy was accused of violating, exercising Executive authority by acting as the prosecutor against Jarkesy and exercising Judicial authority by ruling on the case against Jarkesy. Therefore, because Congress seemingly gave this Executive Agency legislative and judicial power under the Securities Act, the Securities Exchange Act, and the Advisers Act. This constitutes an unconstitutional violation of the Non-Delegation Doctrine.

The final holding pertains to the dual for-cause limitations on the removal of Board members contravene the Constitution’s separation of powers.in violation of Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Company Accounting Board.[4] This is easily the most solid of the three holdings in this case.

The Constitution provides that “[t]he executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.”[5] Since 1789, the Constitution has been understood to empower the President to keep executive officers accountable—by removing them from office, if necessary.[6] This Court has determined that this authority is not without limit.

In Humphrey’s Executor, supra, this Court held that Congress can, under certain circumstances, create independent agencies run by principal officers appointed by the President, whom the President may not remove at will but only for good cause. And in United States v. Perkins[7] and Morrison v. Olson[8] the Court sustained similar restrictions on the power of principal executive officers—themselves responsible to the President—to remove their own inferiors. However, this Court has not addressed the consequences of more than one level of good-cause tenure.[9]

Where this Court has upheld limited restrictions on the President’s removal power, only one level of protected tenure separated the President from an officer exercising executive power. The President—or a subordinate he could remove at will—decided whether the officer’s conduct merited removal under the good-cause standard. Here, the Act not only protects ALJ’s from removal except for good cause, but withdraws from the President any decision on whether that good cause exists.

That decision is vested in other tenured officers—the Commissioners of the Merits System Protection Board —who are not subject to the President’s direct control. Because the Commission cannot remove an ALJ at will, the President cannot hold the Commission fully accountable for the ALJ’s conduct. He can only review the Commissioner’s determination of whether the Act’s rigorous good-cause standard is met. And if the President disagrees with that determination, he is powerless to intervene”[10]

This arrangement contradicts Article II’s vesting of the executive power in the President. Without the ability to oversee an ALJ, a board member, or even the commissioners the President is no longer the judge of the ALJ’s conduct. He can neither ensure that the laws are faithfully executed, nor be held responsible for an ALJ’s breach of faith. These restrictions are incompatible, prima facie with the Constitution’s separation of powers.

It seems highly probable this may explain why ALJs have no qualms about ruling in their own favor in over 90% of all cases. Effectively speaking, the laws which constrain the actions of the DOJ cannot be said to constrain ALJs because they know there are absolutely no consequences for choosing to ignore those laws of constraint.

Supreme Court Question Presented

With a solid understanding of the fifth circuit’s holding in this case lets briefly look at the exact wording of the QP which the Supreme Court would grant petition for cert on, then look at what can be understood from the recent round of oral arguments in this case.

QUESTION PRESENTED:

1. Whether statutory provisions that empower the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) to initiate and adjudicate administrative enforcement proceedings seeking civil penalties violate the Seventh Amendment.

2. Whether statutory provisions that authorize the SEC to choose to enforce the securities laws through an agency adjudication instead of filing a district court action violate the nondelegation doctrine.

3. Whether Congress violated Article II by granting for-cause removal protection to ALJ’s in agencies whose heads enjoy for-cause removal protection.[11]

Oral Arguments

When this case came before the Supreme Court the oral arguments bore little resemblance to the case I had been familiar with both during its oral arguments the year before In the fifth circuit, as well as I the case briefs filed by both parties following the Supreme Courts grant of the petition for cert.

The fifth circuit arguments saw George Jarkesy set the tone for the proceedings with a vigorous and spirited defense of his constitutional challenges. We also got a vigorous debate between the attorneys and the three judge panel about all the key elements that would make up the cases’ alternative holdings.

In the Supreme Court, it was the SEC who were the petitioners which means they set the tone of the hearings. Furthermore, despite the supreme courts arguments being unusually long, at over two hours they only ever discussed the first of three QPs for the duration of the hearing. There was not a single comment or question from the Court addressing non-delegation. The executive appointments issue was only mentioned once, in passing, by Justice Kavanaugh.

That’s it… You would think with an unusually long hearing that only covered a single issue would at least have given us a clear indication about where each Justice comes down on this issue…. But you would be wrong. As we might have expected, most of the Justices seemed unsympathetic to the SEC’s position. But the only clear indications of why they were unsympathetic came from Justices Thomas and Gorsuch.

Justice Thomas staked out a familiar sentiment he has raised in prior cases—

[That] the “public rights” doctrine – the idea that agencies can adjudicate “public” rights without a jury – but cannot apply to any matter depriving an individual of property, so it would be surprising if he accepted the government’s argument here.

Equally unsurprising was Justice Gorsuch’s repeated ridicule the argument of the SEC, that the jury trial right is wholly inapplicable to agency proceedings whenever the public rights doctrine permits Congress to authorize agency adjudication.

For Gorsuch, that amounted to the view that—

The Seventh Amendment would, on your account, dissipate, disappear, whatever verb you want to use… [For him, accepting that result would allow] Congress to overrule the preexisting Seventh Amendment right simply by transferring an action to an agency.

By the end of the argument, Gorsuch had staked out his position with no ambiguity: because the elements of the administrative proceeding are similar to the elements of common-law fraud – “those elements all match up” – Congress can’t move the dispute to an agency without a jury.

“Congress is free to proscribe [fraud] and extend [the common-law action] any way it wants. It just can’t take away a person’s right to be heard before his peers.”

On the other side of this was first and foremost Justice Elena Kagan who would harp on the precedent in Atlas Roofing[12] as not only coming out in favor of the SEC. She insisted “Atlas was so clear, this [Jarkesy] is an easy case.”…

By the end of the proceedings Justices Sotomayor and Jackson were squarely on side with Justice Kagan. Including on the fact that Atlas Roofing alone is, for them, more than enough to find in favor of the SEC here.

The basic facts of Atlas Roofing are as follows:

Pursuant to a Congressional statute, companies were forbidden to maintain unsafe or unhealthy working conditions. The federal government was granted the power to impose civil penalties or get abatement orders in administrative proceedings if a violation was found. The Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission was the agency designated to oversee these proceedings. Atlas Roofing was fined for a violation, and it argued that the administrative proceeding was improper because it violated the Seventh Amendment right to a jury trial.[13]

In Atlas, the Court held:

Congress has the power to give an executive agency authority over adjudicating violations of a new public rights statute, without infringing the Seventh Amendment right to a jury trial.[14]

Much like Justice Gorsuch, she seemed to repeatedly refine her criticism throughout the proceeding, and if Gorsuch’s criticism of the SEC was biting, Elena Kagan’s defense of the SEC is downright acerbic, bordering on hostile.

I take issue with much of Atlas Roofing. First of all I agree with Justice Thomas that this public and private rights distinction is no distinction at all. That anytime the government wants to take someone’s money through fines and penalties the money they are taking is itself private property and any loss of life, liberty or property is entitled to due process of law as the fifth and fourteenth amendment requires.

But even if we set that distinction aside, the workplace safety regulations created by OSHA were novel and had no prior common law equivalent. But Jarkesy was charged with fraud, which could not be more well established as an offense at common law and this makes Atlas Roofing and Jarkesy’s case two different creatures. I see no reason Atlas Roofing should control

However an honest appraisal has to concede that Atlas Roofing is a complex case, that has gotten more complex with later decisions that have watered it down. There are plausible ways to read Atlas Roofing that can be interpreted in favor of the SEC in this case. I have included links to the Atlas Roofing decision and several amicus briefs in Jarkesy that address the applicability of Atlas to Jarkesy for those who want to dig deeper into this case and its relevance to SEC v Jarkesy.

The remaining Justices are less clear in their intentions. Alito gave some indications his position aligns with that of Justice Gorsuch. Otherwise, there is very little (at least from the oral arguments themselves) to give any clear indication of the where remaining Justices stand on this case.

However, I am confident that at least one of the alternate holdings of the fifth circuit will be affirmed. Almost certainly by a solid 6-3 majority.

Total Debunkment

By some accounts, Jarkesy threatens the very foundations of the administrative state.

In this telling, a victory for the respondents will leave the federal government unable to ensure workplace safety, discourage corporate fraud or protect the environment. Jarkesy is unquestionably an important case, but it's just silly to suggest it challenges "the legitimacy of the modern federal government."

The case is really about the continued viability of agency adjudication as a means of enforcing regulatory schemes. This is a big deal, but is hardly threatens the viability of the administrative state nor will it ‘cause another Great Depression’, or ‘the destruction of the New Deal.

Not to mention the timeless classics they trot out for every case or policy they personally disagree with… “If this happens, people will die.”

Their concerns are completely ridiculous. Articles like the one by The Atlantic saying Jarkesy will literally destroy the federal government. Or this article from Vox that suggests reaffirming the fifth circuit in Jarkesy will literally “blow up the government.”

These are not serious arguments and there is no need to even refute them. Common sense alone does that… The reason I bring them up is I think it is important to demonstrate this consistent record of errors in judgement among the administrative state fetishists who always say every administrative agency reform will have catastrophic consequences.

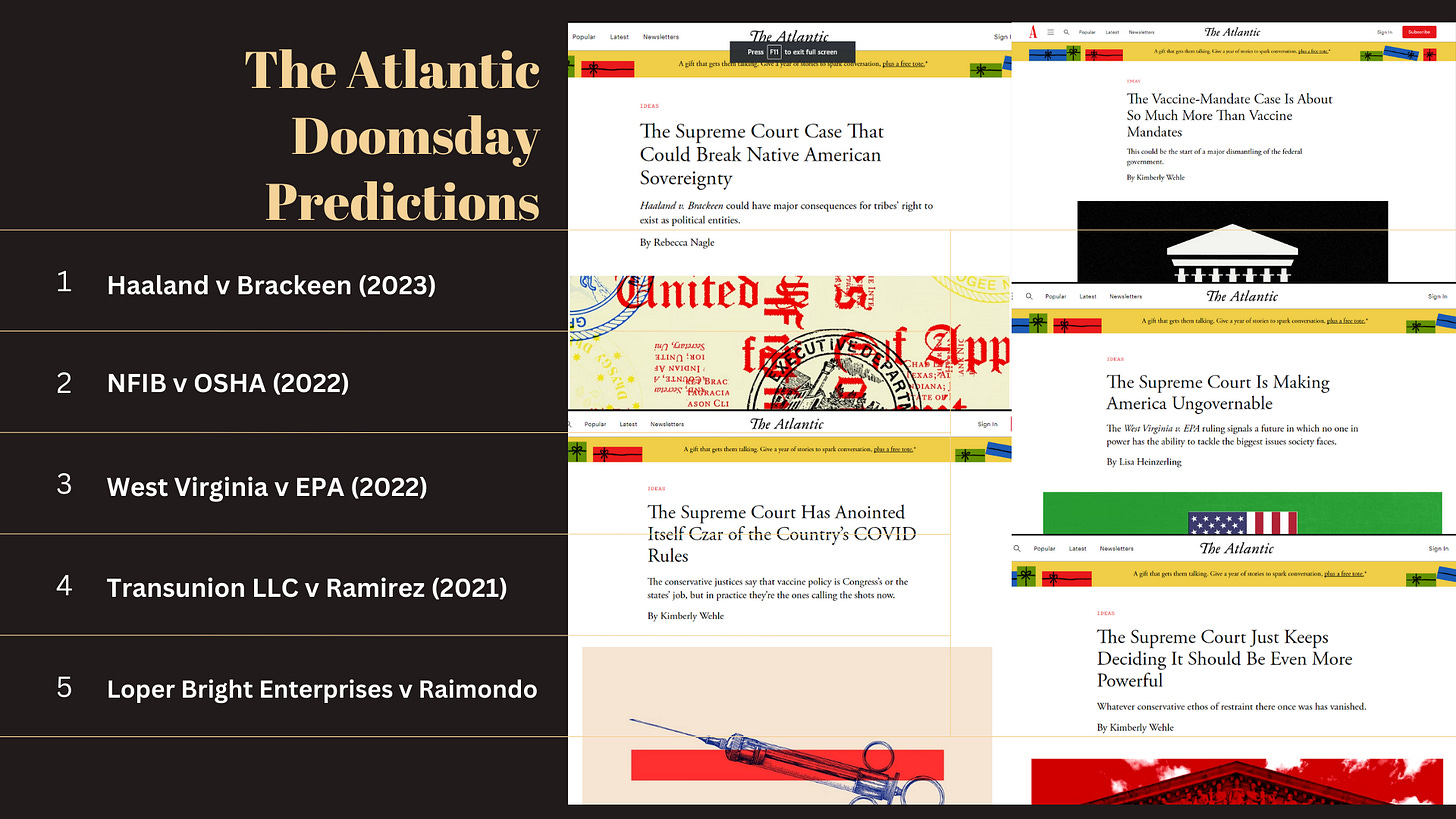

The Atlantic has made these same doomsday claims about the outcomes in Haaland v Brackeen, NFIB v OSHA, West Virginia v EPA, Transunion LLC v Ramirez and Loper-Bright Enterprises v Raimondo…

They are not alone, Vox made the same alarmist warnings for all the same cases.

The same can be said for numerous other publications as well. But when the administrative reforms they feared transpire and the sky never actually falls down, as their Chicken Little-esque warnings predicted-- everyone moves on without learning any lesson from their catastrophic failure of judgement.

And more often than not, it seems real people in the real world who latch onto these warnings and run with them never seem to second guess the overall message, no matter how many times the evidence their beliefs are predicated upon completely falls apart.

So, what will the likely consequences of affirming the fifth circuit be? It will require significant changes in the operations of some federal agencies. In particular, regulatory agencies that enforce their regulatory edicts before agency adjudicators will have to make changes. What those changes are, and how far-reaching the consequences of these changes will be, depends on which challenges succeed, but little in Jarkesy’s case implicates (let alone threatens) the ability of agencies to issue regulations and enforce those regulations in court.

Indeed, the core of Jarkesy's case is that agencies should be required to enforce their rules in federal court, not that they cannot issue rules or seek to have them enforced.

Although most commentary on Jarkesy has focused on the SEC’s claims, and their implications, the more interesting question may be what comes next should Jarkesy prevail. Legal scholar and attorney Johnathon Adler has argued that:

Jarkesy's immediate aim is to prevent enforcement of the SEC's civil penalty order against him, either because the double-for-cause removal of SEC ALJs renders them unconstitutional, or because the SEC should not have been able to prevent Jarkesy from defending himself in federal court in the first instance. Going forward, the question would be how to cure these constitutional infirmities (and whether some cures—such as eliminating for-cause removal protections for ALJs—would create constitutional problems of their own).[15]

There are any number of proposals out there to bring for-cause removal in line with the Constitution. Which proposal the Court would likely adopt is anyone’s guess. In fact, one criticism I have of this case is that this ambiguity of any potential enforcement actions was largely avoidable.

First of all, it’s not common practice for lower courts to issue such broad rulings. Because this is an intermediate appellate Court, who will have neither the first or last word in deciding this case. They did not start with a tabula rasa and have to consider precedent. Precedent they do not have the power to overrule. For example, It is not for lower courts to adjudge the propriety of the Supreme Court’s holding in a case such as Atlas Roofing. It is the duty of the court, and especially the duty of the lower courts to say what the law is, not what the law should be.

This is the nearly universal consensus of Originalist jurists and scholars who say following case precedent, even when that precedent conflicts with the Constitution’s original meaning. With the exception of perhaps three, maybe four Originalist scholars, namely Justice Clarence Thomas, Gary Lawson, Ron Natelson and myself who will argue that where the Constitution and relevant case precedent conflict that we should uphold the former over the latter. But we are well-known crack pots.

My second concern has to do with their resolving all three issues in the case, even though it was unnecessary to do so, which is rare. Issuing alternate holdings almost never happens, and for good reason. Don’t misunderstand me as saying the Fifth Circuit was wrong here. They are correct and I would like to see all three holdings affirmed.

It’s just that brining these three broad resolutions as alternate holdings in one case, especially when coming from an intermediate appellate court was bad strategy. If the goal was to get each of them affirmed on an individual level on constitutional grounds, or as a matter of first principles. this was not a good way to achieve that.

This significantly increases the chance that it will produce a premature resolution of these questions. It also has the potential to force certain questions onto the agenda on a set of facts, or with a given posture that are not the best facts or the strongest posture for what might be the desired outcome.

At this point, all that’s left to do is wait and see how this case shakes out.

Cartago Delenda Est

[1] Constitution of Massachusetts, October 25, 1780

Declaration of the Rights of the Inhabitants of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts—Part I, Article XXX

[2] “The Federalist Number 47, [30 January] 1788,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-10-02-0266. [Original source: The Papers of James Madison, vol. 10, 27 May 1787–3 March 1788, ed. Robert A. Rutland, Charles F. Hobson, William M. E. Rachal, and Frederika J. Teute. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1977, pp. 448–454.]

[3] Jarkesy v. SEC, No. 20-61007 (5th Cir. 2022).

[4] Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Company Accounting Board, 561 U.S. 477, 487-504 (2010).

[5] Art. II, §1, cl. 1.

[6] See generally Myers v. United States, 272 U. S. 52 (1926).

[7] United States v. Perkins, 116 U. S. 483 (1886).

[8] Morrison v. Olson, 487 U. S. 654 (1988).

[9] Free Enterprise Fund, Pp. 10-14.

[10] Humphrey’s Executor, supra, at 620.

[11] 22-859 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION V. JARKESY, Question Presented.

[12] Atlas Roofing Co. v. Occupational Safety and Health Review Comm'n, 430 U.S. 442 (1977).

[13] Atlas Roofing, 420 U.S. 442 (1977).

[14] Id.